Irish Times Head2Head Column Monday July 9th 2007

IS IT TIME TO LEGISLATE FOR ABORTION IN IRELAND?

YES: Fear and hypocrisy must give way to compassion and empathy: the argument for legalising abortion in Ireland is long overdue, argues Ivana Bacik

The issue may have temporarily disappeared from the political agenda, but it remains of immense significance every day to many people in Ireland. We know that more than 5,000 women a year make the journey to England for abortion; about 100,000 Irish women have had abortions in the last 30 years.

Yet in a country obsessed with legal debates about abortion, in which five referendums have been held on the subject in 20 years, the real experiences of women with crisis pregnancies have never been expressed publicly. This culture of silence is not surprising. Fear and hypocrisy have long dominated discussions about abortion, with fearful legislators preferring to leave hard decisions on hard cases to the courts. The result is a situation rooted in hypocrisy.

Everybody knows that planeloads of women travel to England for terminations every year, but everybody pretends that abortion does not exist in Ireland. In fact, Irish abortion rates are comparable to those in any European country. Yet our abortion law is the most restrictive in Europe. Abortion remains a criminal offence under Victorian legislation, dating from 1861, with maximum penalties of life imprisonment for women who have abortions and for those who assist them.

In 1983, a constitutional amendment made the right to life of the unborn equal to that of the pregnant woman. Since then, a series of cases has been taken against women's clinics and students; a series of referendums has been held; litigation has occurred before the European courts.

In the 1992 X case, the Supreme Court ruled that abortion is legal where a pregnancy poses a real and substantial risk to a woman's life, a judgment followed in the 1997 C case, which also concerned a young girl who had been raped and was pregnant and suicidal as a result.

The X case remains law despite a failed attempt by the government to reverse it through referendum in 2002.

During the campaign around that referendum, a woman named Deirdre de Barra wrote to this newspaper explaining that she had been pregnant with a baby diagnosed with a severe abnormality, incompatible with life. She spoke of her anger at an uncaring law that had forced her to travel to England to terminate her pregnancy, and had not allowed her to access the medical treatment required in this country.

Despite an acknowledgment by the masters of the maternity hospitals at the time that abortion should be legal in such cases, the law remains unchanged. In May of this year, a similar case came before the High Court, as a result of which a young woman, known as Miss D, was permitted to travel to England for a termination. Again, she was denied the treatment she needed in Ireland.

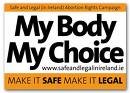

Her case brought into sharp focus once more the lack of compassion in our law towards women with a crisis pregnancy, even those women who will have to give birth to a dead baby if they continue their pregnancy to term. It is now clear that the law is out of touch with changing attitudes. In June, the campaign group Safe and Legal in Ireland published the findings of an opinion poll conducted by TNS/mrbi.

When asked in which circumstances abortion should be legally available in Ireland, the vast majority of those questioned (82 per cent) agreed that it should be available when the pregnancy seriously endangers the woman's life. Three-quarters agreed it should be legal when the foetus cannot survive outside the womb (as in Miss D's case); and 69 per cent where pregnancy results from rape, or where the pregnant woman's life is at risk due to a threat of suicide.

This opinion poll, together with others conducted in recent years, show that the values of compassion and empathy have taken over from the culture of fear and hypocrisy.

Legal change is now necessary to reflect this. As a first step, legislation should be enacted under the X case to specify the conditions under which life-saving abortions may be carried out here.

Clearly, that alone would not resolve the real issue. Legislating for X would not address the needs of women like Miss D, or the needs of the many thousands of others who make the journey abroad each year in crisis.

As we enter the term of a new Dáil, we should insist that our elected representatives take responsibility for legislating in a fair and reasonable way for the rights of our citizens.

We must look to European standards in reproductive healthcare, and investigate ways of changing the law in a compassionate and sensible way, so that the real needs of women in crisis pregnancy are addressed.

Ivana Bacik is Reid Professor of Criminal Law, Criminology and Penology, Trinity College Dublin and spokesperson for the Safe and Legal (in Ireland) Abortion Rights Campaign.

IS IT TIME TO LEGISLATE FOR ABORTION IN IRELAND?

No: A decent society must recognise the humanity of the unborn, argues Berry Kiely .

The campaign for legal abortion achieved its aim in Britain with the introduction of the Abortion Act there 40 years ago. Many medical and technological changes have since occurred, giving us a valuable opportunity to assess the social and human costs of abortion. In 1967 one could have pleaded blindness to the humanity of the unborn; in 2007 this is no longer possible.

The fundamental basis of our society and its laws are rooted in the principle that every human life has intrinsic value irrespective of age, sex, health, race, creed or any other factor that differentiates one from another. Proponents of abortion want the unborn child to be an exception to this rule. To do this they resort to the tactic of denying the humanity of the unborn. But recent technological advances make it increasingly difficult to defend that stance.

Former head of obstetrics and gynaecology at King's College School of Medicine, London, Prof Stuart Campbell, commented recently: "There is something deeply moving about the image of a baby cocooned inside the womb. At 11 weeks we can see them yawn, and even take steps. Understandably, these incredible images have influenced the debate on abortion. I pioneered the 4-D scanning technique in the UK and it has certainly caused me to question my own opinions."

Not only 4-D ultrasound images but also the debate around partial-birth abortion and the survival of many premature infants are eroding the pro-choice rhetoric. The number of abortions in the US is in steady decline. In the UK it is increasingly difficult to find doctors willing to carry out abortions, as it runs contrary to their desire to save life. The findings of the latest pro-choice polls here, indicating support for abortion in certain circumstances, are not surprising. The poll questions make no distinction between ethical interventions in pregnancy to save the life of the mother and induced abortion where the life of the unborn child is directly targeted. To clarify the difference: in ethical interventions one hopes the child will survive; in abortion one wants the child to die.

When people are asked the straight question of whether they wish to see abortion legal in Ireland, the answer is at variance with the recent pro-choice survey. In a Millward Brown/IMS poll, commissioned by the Pro-Life Campaign in March this year, 66 per cent of those who expressed an opinion were opposed to the Dáil legislating for abortion. Little by little, the rhetoric that proposes abortion as a positive option for women is being challenged. Speaking recently from personal experience, Dr Alveda King, niece of assassinated civil rights leader Martin Luther King jnr, said: "We mothers suffer tremendously, and our families suffer." Her sentiments are echoed by other women who have had abortions. Groups such as Silent No More and books such as Giving Sorrow Words by Melinda Tankard Reist are shedding light on the experiences of women who regret their abortions.

Most early studies of the effects of abortion on women were limited to the immediate post-abortion period. Now long-term studies are giving a clearer picture. One such study was published in 2006 in the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry.

This was a 25-year longitudinal study which showed that women having an abortion had elevated rates of subsequent mental health problems including depression, anxiety, suicidal behaviours and substance-use disorders. This association persisted after adjustment for confounding factors. The main author of this study, Prof David Fergusson, admitted: "I'm pro-choice but I've produced results which, if anything, favour a pro-life viewpoint".

An earlier study in Finland examined data from 1987-2000 and highlighted the fact that the suicide rate was almost seven times higher in women who had abortions compared with those who gave birth. This is particularly relevant to the Irish situation given the calls for abortion to be legalised on grounds of threatened suicide.

There is a fundamental distinction between necessary medical treatments in pregnancy to save the life of the mother and induced abortion where the intended target is the life of the unborn child. If there was any truth in the assertion that induced abortion was medically necessary, our maternal mortality figures would be higher than those of countries with abortion: in fact our maternal mortality is considerably lower than in the UK.

Recently, we have seen where the abortion of a child with a lethal abnormality was considered by some as a positive option. This attitude is hard to reconcile with our normal approach to disability and terminal conditions. If society decides to end the lives of children based on their disability, it undermines their right to equal respect. A truly life-affirming society should give all positive supports to mothers and families of disabled children, not just during pregnancy, but throughout their children's lives.

Dr Berry Kiely is a spokeswoman for the Pro-Life Campaign

Tuesday, July 10, 2007

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment