Wall St Journal

· When Justices Prefer Not to Judge: Court May Pass on Abortion Again

By PAULA PARK

A European court may decide whether a woman has a basic right to abortion to preserve her health. Or, some observers fear, it may avoid the issue, as it has in the past.

The European Court of Human Rights was established to uphold rights to life, privacy, freedom of speech, religion and the like. The court has one justice from each of the 47 nations that signed the European Convention on Human Rights. It rules on cases that applicants bring when they feel they cannot get adequate legal redress in their home countries.

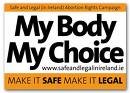

Pro-choice supporters protest Ireland's abortion laws, among the strictest in Europe, outside Dublin's High Court.

But for years the court has essentially turned a blind eye to Ireland's abortion laws, considered among the most restrictive in Europe. Critics say that helps perpetuate an inequitable patchwork of rules across the region.

Regardless of which way the court ultimately rules, its delay highlights the complexity of what would seem a simple question: Aren't judges supposed to judge?

Siobhán Mullally, senior lecturer at the University College Cork Faculty of Law, says that by declining to hear certain cases, the justices can skirt a reckoning with the most central questions on abortion. "So far the court has been very cautious," she says.

The current case, A.B. and C. v. Ireland, was brought by three Irish women who received abortions in England for health reasons -- one had cancer -- and suffered medical complications upon their return to Ireland. The women say they were uncomfortable seeking medical treatment, both before and after the abortions, because of Ireland's laws, including a 1995 statute that applies criminal penalties to anyone giving information or assistance that promotes the procedure.

In addition, an abortion ban is written into the Irish constitution, which essentially states that the right to life of the fetus is equal to that of the mother. The Irish Supreme Court ruled in 1992 that abortion is legal if necessary to save a woman's life, but no laws were made to define when an abortion is necessary. The applicants argue that the Irish laws infringed on their rights to life, privacy and freedom from discrimination.

Prof. Aurora Plomer, an expert in bioethics at the University of Sheffield's School of Law, in Britain, cites the court's language that its charter "is intended to guarantee not rights that are theoretical or illusory but rights that are practical and effective."

The judges have stepped back from the issue before. They refused to examine whether a fetus is protected in cases brought from other countries. And they declined to hear an earlier challenge to Ireland's law. Applicants must exhaust all legal remedies in Ireland before seeking redress in Strasbourg.

The Catch-22: how to exhaust those remedies amid vague or conflicting laws before a dangerous due date arrives -- or it becomes too late to abort.

The U.S. Supreme Court, too, has shrunk from tough issues, though it is often accused of being too activist. Erwin Chemerinsky, a constitutional scholar and founding dean of the University of California-Irvine School of Law, cites early challenges to the ban on interracial marriage as an example. In a more recent instance, in 2004, the high court used procedural grounds to avoid ruling on a challenge to the 'one Nation under God' phrase in the Pledge of Allegiance.

It is a topic of a longstanding debate in U.S. history. Some say it's good for the justices to wait, allowing time for the political process to resolve issues. Others argue that it's the court's job to make the tough calls.

The European justices could make their own case. By requiring the applicants to exhaust civil remedies in their home countries first, they avoid exceeding their mandate. While 43 of the 47 states have laws allowing abortions for health reasons, four do not, and those bans are strict.

But the court was created, in part, to resolve conflicts. Standing pat can sustain inequity, some observers say. A woman could die in one country from complications from a pregnancy, where another state would have protected her life.

Prof. Richard Kay of the University of Connecticut School of Law says that in a landmark 2004 case, the court noted that there was no European consensus on when life begins. That consensus is critical for the court, Mr. Kay says, because, unlike the U.S. Supreme Court, the European court has no binding authority. Member states rarely resist its decisions, but enforcement is political, not legal.

Mr. Kay says the court could rule on Irish abortion and that even if the government disagreed, it would comply. It's a sophisticated country, he says. It follows the rule of law.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment